Introduction

Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) is the most common spinal deformity and has unclear aetiology in 70 to 80% of cases [1]. AIS is a three-dimensional deformity characterised by deviation of the spine in the frontal and sagittal planes, with a degree of vertebral rotation [2]. Spinal deformity with a Cobb angle > 10° in the frontal plane is considered scoliosis [3–5]. The disease affects around 5% of the adolescent population and is more prevalent in girls than boys, with a ratio of 1.5–3:1 [6]. A study reviewing AIS across 13 countries found a higher prevalence in regions at high northern latitudes than in lower latitudes [7]. For instance, AIS prevalence was 5.2% in Germany [8], 1.0% in Singapore [9], 1.4% in Brazil [10], and 1.7% in Greece [11]. These differences could be attributed to the methods used, statistical analysis, and the sample evaluated.

AIS has multiple physiological and psychological effects on adolescent life, with spinal deformity causing discomfort, pain [12], low back pain [13], respiratory dysfunction [14], poor physical activity performance [15], and cosmetic concerns [16]. The psychological effects of AIS include decreased health-related quality of life, poor self-esteem, and limited self-image [17, 18]. Recent studies examining the negative impacts of social determinants of health on patient outcomes identified several factors that may influence health in those with chronic disease, including race, socioeconomics, insurance eligibility, and childhood opportunity index [19, 20].

Only 20% of scoliosis cases have a known cause (neurological, congenital, and syndromic), while the remaining 80% with unknown causes fall within idiopathic scoliosis [21,22]. Although AIS aetiology is not fully understood, multiple factors have been investigated to help understand its occurrence and evolution. Such factors include genetic components, vestibular dysfunction, endocrine disorders, muscle and connective tissue imbalance, and improper mineral metabolism [23–25].

Bone mineral density (BMD) is a non-genetic component that may influence idiopathic scoliosis progression, as bone quality is essential for bone mechanical stability [25]. Bone strength is negatively affected by osteoporosis, and the prevalence of AIS with osteoporosis is about 20–38% [26–28]. Numerous factors, including vitamin D, parathyroid hormone (PTH), and calcitonin levels, affect calcium-phosphorus metabolism and homeostasis, which affect bone growth and degeneration [29].

Recent studies have suggested a possible causal link between decreased vitamin D levels and AIS [30–32], with evidence that vitamin D deficiency may contribute to AIS pathogenesis. As a result of calcium-phosphate metabolism being poorly regulated in the skeletal system, AIS development is likely to be influenced by it [31]. Previous studies have reported that Cobb angle could be affected negatively by a lack of vitamin D in AIS patients [30, 31, 33], with the relationship primarily attributed to the role of vitamin D role in postural balance, which correlates positively with hip BMD and negatively with Cobb angle. According to Batista et al., skeletal maturity and growth potential are critical in scoliosis curve progression, and continuous monitoring of AIS patient pathology and vitamin D levels is prudent [34]. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the correlation between vitamin D deficiency and AIS development to provide basic knowledge about idiopathic scoliosis pathogenesis that could be used for rehabilitation programme recommendations and early detection plans. Based on the previously published literature, we hypothesised that there is a correlation between vitamin D deficiency and AIS development.

Subjects and methods

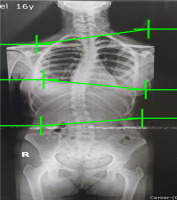

This retrospective cohort study examined 130 medical records of adolescent patients at the Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation Centre, South Valley University, Egypt, between May 2021 and October 2022. Patient clinical and demographic data were extracted from medical records, including age, gender, height, weight, serum vitamin D level, and Cobb angle. The inclusion criteria were patients diagnosed with scoliosis (Cobb angle ≥ 10°), and the exclusion criteria were patients with a history of walking difficulties, including congenital postural abnormalities, lower limb discrepancy, congenital anomalies, hemivertebrae, muscular dystrophy, and spina bifida. Scoliosis was identified when the Cobb angle was ≥ 10°, which was calculated by measuring the largest spinal curve, taken from the upper-end vertebra to the lower-end vertebra, using X-ray records. An experienced radiologist was responsible for measuring and reporting the Cobb angle. Patients had a choice of morning, afternoon, or evening sessions for laboratory measurements. Fasting was required for 12 hours before the morning examination or six hours before the afternoon or evening examination. Vitamin D levels [25-hydroxyvitamin D (25 (OH) D] were determined from frozen serum samples using electrochemiluminescence immunoassays (Roche, IN, USA). According to the American Academy of Paediatrics, vitamin D is deficient when < 20 ng/ml and sufficient if > 20 ng/ml [35]. Figure 1 shows a sample of the Cobb angle measurement of a 13-year-old boy.

Statistical analyses were conducted on demographic data, vitamin D levels, and the Cobb angle. The Cobb angle and vitamin D levels were evaluated by an independent samples t-test, whereas gender was analysed using the chi-squared (χ2) test. The correlation among vitamin D levels, age, weight, and Cobb angle was investigated using Pearson’s correlation. Statistical significance was established by a p-value lower than 0.05 and 95% confidence intervals (CI). JAMOVI v.2.3.21 software was used for analysis.

Results

A total of 130 (45 boys and 85 girls) subjects aged 7–18 years old (mean = 13.1; 95% CI = 12.6–13.6) with a diagnosis of AIS were assessed and managed at the Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation Centre, South Valley University, Egypt, between May 2021 and October 2022. The mean vitamin D levels were 10.3 ng/ml ± 4.76 (95% CI = 9.4–11.1), weight was 47.4 kg ± 9.63 (95% CI = 45.6–49), and Cobb angle was 16.8 ± 5.79° (95% CI = 15.8–17.8). Table 1 presents a demographic description of the sample.

Table 1

Demographic description of the sample (n = 130)

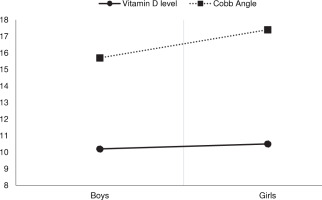

Figure 2 presents the difference in vitamin D levels and Cobb angle between boys and girls. There was no substantial difference in vitamin D level (p = 0.77) or Cobb angle (p = 0.10) between boys and girls.

The sample was divided into juvenile (n = 18) and adolescent (n = 112) groups based on the age of AIS onset. When comparing subgroups and gender, analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed no difference between the two subgroups for vitamin D level (F(1, 126) = 0.28, p = 0.59) or Cobb angle (F(1, 126) = 0.004, p = 0.95) (Table 2).

Table 2

Comparison of Cobb angle and vitamin D levels between juvenile and adolescent subgroups

Table 3

Comparisons between the Cobb angle and vitamin D levels for a Cobb angle lower and greater than 10°

| Cobb angle | n | Mean (SD) | 95% CI | Min | Max | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lower | upper | ||||||

| > 10 | 123 | 10.1 (4.70) | 9.3 | 11.0 | 3.4 | 23 | 0.14 |

| < 10 | 7 | 12.9 (5.49) | 7.8 | 17.9 | 5.3 | 18 | |

Table 4

Vitamin D level correlation with age and Cobb angle

Table 3 shows that serum vitamin D declined with the Cobb angle, though there was no statistically significant difference (p = 0.14) when using a cut-off of 10° for the Cobb angle to define idiopathic scoliosis.

Table 4 presents the correlations between vitamin D level, age, Cobb angle, and weight. Vitamin D was positively correlated with age (r = 0.45, p < 0.001) and weight (r = 0.51, p < 0.001). However, only a weak positive correlation was found between vitamin D level and Cobb angle (r = 0.11, p = 0.18). Figure 3 provides a graphical representation of the correlation between vitamin D level, age, Cobb angle, and weight.

Discussion

The optimum therapeutic strategies for AIS depend on identifying the most reliable and plausible quantification of clinical indicators, such as the Cobb angle, and associated risk factors, such as vitamin D level [23]. AIS aetiology has been the subject of several theories, though little information is available regarding how vitamin D deficiency or insufficiency is associated with the emergence of scoliotic curvature. Therefore, the present study measured vitamin D levels and explored their association with the development of AIS.

The study findings demonstrate that serum vitamin D3 levels fell below the reference range recommended by the American Academy of Paediatrics and US Endocrine Society (< 20 ng/ml or 50 nmol/l) [36] for scoliotic male and female adolescents, with no sex-specific differences. However, the development of scoliosis (i.e., a Cobb angle increase by > 10–15°) (5) was not significantly correlated with vitamin D3 deficiency. This might be accounted for by the study’s intentions to explore early alterations in Cobb angle and their relationship to vitamin D levels. While the average Cobb angle observed in the current sample was close to the minimum determinant of scoliosis, the association may become clearer with greater certainty over time as the scoliotic curvature evolves.

The current findings corroborate prior research on vitamin D levels in adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis to some extent. In a retrospective study, Balioglu et al. [30] analysed the levels of vitamin D in 229 adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis and 389 age-matched controls. According to their findings, there was a significant decline in vitamin D concentration in the scoliotic adolescents compared to their healthy controls, without any sex effects, suggesting a potential vitamin D resistance in the scoliotic group. Comparably, the current study detected insufficient vitamin D levels relative to the reference ranges derived from the normal population, though no healthy individuals were used for a direct comparison. Balioglu et al. [30] also looked at the relationships between vitamin D levels and several factors, including sex, Cobb angle, serum calcium, phosphorus, and alkaline phosphatase levels in the scoliotic group. In contrast to the current findings, they noted a significant negative correlation between vitamin D and Cobb angle and a positive correlation with calcium levels, showing potential for vitamin D involvement in AIS aetiopathogenesis.

In the same context, Kalra and Aggarwal [37] conducted a comprehensive review to address the issue of vitamin D deficiency and describe its development and role in human physiology. Vitamin D levels were lower in adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis, while vitamin D and Cobb angle were negatively correlated. These findings raise the possibility that vitamin D contributes to the emergence of AIS and define significant prospects for upcoming mechanistic and clinical research on AIS. Goździalska et al. [32] investigated the level of vitamin D3 alongside other factors in a cross-sectional study of two groups of adolescent girls with scoliosis and age-matched scoliosis-free controls. They reported significantly lower vitamin D levels in the scoliotic group than in the nonscoliotic group and inferred that vitamin D deficiency can be involved in AIS. In another cross-sectional study, Batista et al. [34] tried to establish whether an association exists between serum vitamin D levels and AIS and detected low vitamin D levels in 91% of AIS patients.

AIS is a heterogeneous, multifaceted condition with inherited and environmental influences on its aetiopathogenesis [38, 39]. The findings of the present study confirm that vitamin D deficiency is prevalent among scoliotic adolescents (despite the association of vitamin D and Cobb angle being non-significant), as was the case for osteopenia in a prior study [30]. As such, it remains possible to hypothesise that vitamin D deficiency and/or insufficiency affect scoliosis development in adolescents, presumably through its impact on the regulation of fibrosis [40], postural control [41], and bone metabolism [30]. If the debate is to be moved forward, an improved understanding of the association of vitamin D deficiency with AIS could be achieved in additional studies using larger samples stratified based on the Cobb angle.

The current findings have significant implications for understanding how adequate vitamin D is critical for adolescents in general and those with idiopathic scoliosis in particular, given its role in calcium and phosphorus metabolism and the potential impact of its deficiency on skeletal structures [30]. There is general agreement regarding the value of vitamin D testing, and adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis would benefit from having sufficient serum levels to enable early diagnosis and consistent care. Adolescents with scoliosis should learn about effective strategies to enhance vitamin D, such as spending time in the sun, consuming the best natural vitamin D food sources, and engaging in physical activity programmes.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the relationship between vitamin D and Cobb angle in AIS in the Middle East. Recruiting participants from a healthcare centre with a valid and experienced radiologist to measure and evaluate the Cobb angle adds strength to the study. However, there are limitations on how broadly the present findings could be applied. A definitive conclusion would have been established if data from the scoliosis patients had been compared to age and gender-matched healthy individuals from the community, even though participants had lower vitamin D than reference values. It is unfortunate that the study did not include adolescents with a wide range of Cobb angle measurements, which could have allowed classification of the condition on its severity and a more comprehensive analysis of vitamin D level and its association with different angulations (i.e., mild, moderate, and severe scoliosis). Therefore, further analyses accounting for these variables will need to be undertaken. The sample size is another source of uncertainty, as even though data from 130 adolescents seems sufficient, a larger sample size might have provided more definitive evidence.

Conclusions

According to the results of the present study, there was no significant association between scoliosis onset and vitamin D level in the current sample. Nonetheless, adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis had serum vitamin D levels below the recommended level. In adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis, screening for vitamin D inadequacy or insufficiency should be considered, especially since this information will allow for early detection programmes and the creation of preventative and rehabilitation measures.