Introduction

The vestibular system is essential for maintaining balance and posture, navigation, orientation, and recognising motion [1]. Vestibular dysfunction can originate from the central or peripheral vestibular systems, with unilateral peripheral vestibular dysfunction (UPVD) being a common manifestation [2]. Unilateral vestibular hypofunction is when the vestibular system is no longer functional on one side [3], where the other side balances the whole body. This decompensation on one side leads to dizziness, loss of balance, unsteady gaze and gait, impaired navigation, and spatial orientation, which may harm a person’s ability to perform activities of daily living (ADL) and work [4].

Vestibular physical therapy (VPT) exercises help people with vestibular hypofunction feel less dizzy and see better when moving their heads, which improves postural stability and lowers the risk of falls [5]. The Cawthorne-Cooksey exercise is a typical VPT exercise designed to decrease the effects of motion-induced vertigo [4]. Cawthorne-Cooksey exercises allow the individual to progress from simple head movements only to the head with either open or closed eyes exercises. They also include bending, sitting, standing, throwing a ball, walking, and ascending stairs, during which the subject progresses from lying down to sitting, standing, and then walking [4]. Acetazolamide has a positive association with improvement of symptoms of visual vertigo, with a trend for greater improvement in more dynamic movements in the environment [6].

Repetitive Transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) are two brain stimulation techniques that have been suggested as potential treatments for a range of neurological diseases, including motor deficits and balance issues [7]. rTMS is a more focused tool than tDCS because it directly affects brain networks [8]. Among other types of brain stimulation, rTMS is the most precise therapy with good control over the stimulation parameters [9].

Techniques for repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) entail rapidly stringing together many TMS pulses one after another. This technique is applied in clinical and research settings because it can result in brain activity alterations lasting longer than the TMS treatment. There have been reports of excitability changes that last for several hours. The effects of rTMS protocols seem to depend on how quickly the pulses are delivered; high-frequency rTMS protocols deliver pulses at a rate of > 5 Hz, whereas low-frequency rTMS protocols deliver pulses at a rate of < 1 Hz, which tends to induce inhibitory effects in the brain [10]. rTMS has been successfully used to treat several neurological and psychiatric disorders [8]. To our knowledge, the advantages of rTMS in patients with UPVD have yet to be elucidated. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine whether adding rTMS to VPT exercises could have an impact on specific vestibular and self-reported functional recovery outcomes in patients with UPVD.

Subjects and methods

Design and settings

This study used a prospective evaluation and interventions, double-masked randomised controlled trial design. Before inclusion in the study, participants were given information about the study and were required to sign a written agreement.

Sample size calculation

The projected sample size was determined before the study using the G*power tool 3.1.9 (Heinrich-Heine-University, Düsseldorf, Germany). F tests (MANOVA: Special effects and interactions) revealed Type I error = 0.05, power (1-b error probability) = 0.90, and effect size (V) = 0.66 obtained for independent canal weakness (primary outcome), which is the variable from other studies [11], with a comparison of 2 separate groups for three different outcomes. The minimum expected sample size was 35 patients. A total of 40 patients were required to allow for a 10% dropout.

Participants

The inclusion criteria were age between 30 and 60 for both sexes and a sickness duration of 4–32 months for chronically uncompensated unilateral peripheral vestibular weakness.

The exclusion criteria were alcohol abuse, electrical device implantation, epilepsy, cognitive dysfunction, cardiac dysfunction, acute and bilateral peripheral vestibulopathy, central vestibular disorders, benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, vertigo of vascular or cervical origin, and prior ear surgery.

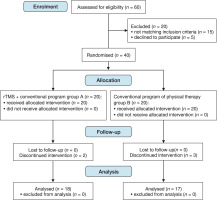

The patients were referred by an audiologist/physician. This study used a 1:1 randomisation method (intention-to-treat analyses). Thirty-five eligible patients with UPVD were randomly assigned to two groups: study (n = 18) and control (n = 17). Five participants declined to take part because they would not be followed up to assess long-term effects. A participant flowchart is shown in Figure 1.

Interventions

Identical vestibular physical therapy activities were administered to the patients in both groups; however, only those in the study group received rTMS. The interventions consisted of three sessions each week for a total of four weeks.

Vestibular physical therapy exercises

These took the form of Cawthorne-Cooksey-designed exercises [12]. Cawthorne-Cooksey exercises consist of four sequential progressions of increasing difficulty: bed exercises including eye movement (upgaze, downgaze, lateral gaze, centre gaze on a one-foot distant object) and head movement (flexion and extension, head-turning both sides with eyes open and then repeated with eyes closed). This was followed by sitting exercises, including shoulder shrugs, bending forward, turning the whole body to the right and left, and picking something up off the floor. In the third progression, the latter exercises were repeated in a standing position, followed by standing up from a seated posture and turning around in between. Other exercises included throwing a ball between the hands above eye level and below knee level. Fourth, ambulatory exercises, in which the patient encircled a person seated in the middle and while the patient was walking around circle, they were given a ball to throw back to the giver. When performing any activity that includes throwing and catching a ball, walking around with one eye open and the other closed, ascending stairs with one eye open and the other closed, etc., the speed of each exercise increased from slow to fast. Patients progressed from bed exercises to sitting or standing exercises at various speeds depending on the severity of their vertigo. For a total of 20 min, patients performed vestibular physical therapy activities, pausing for rest between sets [13].

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS)

The study group also underwent rTMS plus vestibular exercise. High frequency (10 Hz) rTMS was applied to the dominant dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) using a Magstim Rapid Magnetic Stimulator (Magstim Company, Whitland, Wales, UK). The patients were seated in a chair, with their arms and legs at their sides and their heads held firmly during the treatment. A 50-volt motor-evoked response in the abductor pollicis brevis (APB) muscle was elicited in five trials. This was defined as the motor threshold (MT), determined before each session. The DLPFC of the dominant hemisphere is situated on the scalp 5.5 cm in front of the hot point of the opposite APB muscle in the parasagittal plane [11]. During the first mapping procedure, the centre of the coil was tangential to the scalp, with the coil situated at a 45° lateral diagonal location perpendicular to the central sulcus [14].

Regarding the high-frequency stimulation, 100% MT was used to generate 1800 pulses that were administered in the form of 45 trains at 10 Hz, each of which contained 40 pulses and lasted 4 s. The intertraining time was 26 s [11]. The stimulation was administered for 22.5 min three times each week for four weeks.

Evaluation

History-taking and physical examination

At the beginning of the study, an audiologist conducted a thorough medical history interview and clinical examination to determine the cause of the vestibular dysfunction, distinguish between central and peripheral causes, select patients who met the inclusion criteria, and exclude patients who met any of the exclusion criteria.

Outcome measures

All outcome measures were taken at the beginning of the intervention and four weeks later. The Dizziness Handicap Inventory (DHI) and Vestibular Disorders of Daily Living Scale served as supplementary outcome measures, and videonystagmography (VNG) served as the primary outcome measure for canal weakness (VADL).

Canal weakness

Unilateral vestibular canal weakness was evaluated using VNG. The latter was used with caloric testing to investigate eye movements using Micro Medical Visual Eyes for Windows, version 8.1.4 [15].

Dizziness Handicap Inventory (DHI)

In clinical and research contexts, the DHI is widely used to assess disabilities associated with dizziness [16]. This self-report questionnaire was created to measure how much dizziness caused by their vestibular system dysfunction the patients perceive as a limitation (Jacobson and Newman, 1990). In this study, the Arabic version of the DHI was used. It has strong reliability and validity [17].

Vestibular Disorders Activities of Daily Living Scale (VADL) (Arabic version)

The scale employs a questionnaire form suitable for scoring disabilities self-perceived during daily activities ranging from 1 to 10 (1 = independent, 10 = very difficult) [18]. The form consists of instrumental, functional, and ambulatory subscales. The instrumental, functional, and ambulatory subscales were used to investigate the self-perception of socially complex tasks, primary self-maintenance chores, and mobility-related skills [19].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using the SPSS application (Version 25) for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data are presented as means and standard deviations for age, weight, height, body mass index (BMI), canal weakness, DHI, and VADL. The Breusch–Pegan and Levene’s tests were used to decide between parametric and non-parametric tests. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and the Shapiro–Wilk test were used as normality tests to assess the distribution of variables. The chi-squared test was used to evaluate sex differences between the two groups. A mixed-design 2 × 2 MANOVA test assessed the differences within and between groups. An effect size f2 (V) = 0.66 was obtained for the independent canal weakness variable from other studies [11]. All tests showed statistically significant results at the probability level p = 0.05.

Results

At baseline

Table 1 displays the main traits of the patients in the two groups. The anthropometric and demographic factors (Table 1) and the outcome measures were not statistically significant between the two groups (Table 2).

Within-group analysis

As seen in Table 2, the study group experienced significant improvements in VADL, DHI, and canal weakness compared to baseline. Only the DHI and VADL showed statistically significant results.

Table 1

Baseline characteristics of patients

Table 2

Comparison of the outcome measures within and between groups

Comparison between groups

As shown in Table 2, the study group considerably outperformed the control group regarding canal weakness, DHI, and VADL (p = 0.05) with effect size f2 (V) = 0.66.

Discussion

Evolving research on the use of rTMS for treating various neurological diseases has recently been published. To our knowledge, rTMS has yet to be the subject of any previous study investigating its efficacy as a UPVD treatment. The objective of this study was to assess how high-frequency rTMS affected individuals with UPVD canal weakening, the level of dizziness, and involvement in everyday activities.

The current study shows that, in UPVD patients, the combination of high-frequency rTMS and VPT exercises led to noticeably more significant improvements in canal weakness, intensity of dizziness, and daily activity performance than VPT exercises alone. When combined with physical and behavioural therapy, high-frequency rTMS promotes cortical reconfiguration and learning consolidation in specific neural networks, modifies synaptic plasticity, and enhances vestibular network cortical excitability. High-frequency rTMS uses a series of repeated magnetic pulses to modify cortical activity and alter neuronal excitability [20].

Non-invasive transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), a neuroelectrophysiological technique that emerged in recent decades, has attracted clinical attention [21]. The goal of exciting or inhibiting the local cerebral cortex can be achieved by using repetitive stimulation with different frequencies, namely repetitive TMS (rTMS). rTMS was quickly applied in depressive disorder therapy, commonly at high frequency, e.g., 10 Hz or theta burst, to the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex [22].

The general improvement in the research group can be explained by the fact that stimulating brain regions such as the DLPFC affects the entire brain network, not just the local stimulation site. Notably, patients with UPVD experienced better outcomes with high-frequency rTMS. These findings are those of previous studies [23].

This study showed that canal weakness improved dramatically only in the study group. A possible explanation is that rTMS altered several inhibitory and excitatory connections between the lateral cerebellum and the contralateral prefrontal region. The primary impact may be due to the short rTMS action on the contralateral cerebellum and ipsilateral prefrontal cortex [24]. rTMS has been shown to have neuromodulator effects on the default mode network [25]. Remote sites that are physically or functionally linked to the network and locally stimulated sites can also show a response to rTMS stimulation [23].

The current study also showed that the dizziness levels in both groups significantly decreased from baseline, with the study group showing the most significant improvement. The study group’s findings could be confirmed by [26], who investigated patients with Mal de Débarquement Syndrome (MdDS) utilising high-frequency stimulation over the left DLPFC and sham rTMS and discovered rTMS-induced improvement in the DHI. Furthermore, [27] reported that rTMS over the left DLPFC in a 61-year-old man with a history of traumatic brain injury resulted in a significant decrease in the clinical importance of a dizziness-related handicap from 40 to 21 points on the DHI.

In contrast, [23] used multimodal neuroimaging data to test the effects of rTMS modulation in patients with MdDS. Their results revealed that symptoms measured using the visual vertigo analogue scale did not improve in 40% of patients, while symptoms increased in 30%.

The significant improvement in DHI after therapy in this study could imply that employing rTMS in addition to vestibular rehabilitation activities can assist patients with UPVD in feeling less dizzy. Interventions in brain regions that are a component of the circuits that generate oscillation-related sensations are a revolutionary treatment strategy, according to [28].

This study is a pioneer in detailing the beneficial effects of rTMS in patients with UPVD who participate in ADL. It was demonstrated that the study group’s VADL improved considerably compared to the control group.

There are two possible explanations for these findings. According to the first hypothesis, improved functional competence is mainly caused by decreased vertigo intensity [29]. Accordingly, [30] observed that it is essential to consider the patient’s level of independence and self-perception of dizziness when choosing treatment modalities for vestibular rehabilitation and in everyday practice.

The second idea proposes that people’s daily activities are influenced by factors other than spatial orientation, postural control, and dizziness management, which impact how people engage in daily activities. This theory can be understood by considering [31], who reported that neuromodulation could dramatically influence postural control and motion perception because of the widespread cortical projections of the vestibular system and its connections to networks involved in cognitive and affective control.

Limitations

The current study had several limitations. The first restriction was the absence of follow-up to assess long-term effects. Additionally, there were few outcome measures, and visual vertigo and its connection to canal weakness and the degree of impairment were not evaluated. A short self-assessment of mood level should have been conducted. Despite these drawbacks, this study has several advantages, one of which is using a less invasive neuromodulation technique, such as rTMS, in UPVD therapy regimens. Additionally, videonystagmography was used in this study as an impartial method for monitoring vestibular healing.

Applications

Adding rTms to ordinary vestibular rehabilitation programs (Cowthrone-Cooksey exercises) can have a more beneficial effect on overall recovery, regaining the ability to participate and integrate more functionally in activities of daily living, and improving the quality of life of patients with peripheral vestibular dysfunctions.

Moreover, our study showed that rTMS, which is considered a well-established neuromodulation modality in the field of neurorehabilitation, is accessible to healthcare facilities and can be implemented as a part of rehabilitation in the field of audio-vestibular interlinked with the physical therapy vestibular rehabilitation field, has a superior effect when compared to ordinary vestibular exercises that improve canal weakness, dizziness and participation in activities of daily living.

Conclusions

In individuals with UPVD, the combination of rTMS and VPT exercises may result in noticeably more significant improvements in canal weakness, DHI, and VADL than VPT exercise alone. It can be argued that adding rTMS to vestibular rehabilitation regimens could enhance vestibular and functional recovery outcomes. Further rigorous studies are required to verify these findings.