Introduction

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries are prevalent among athletes and active individuals, often requiring surgical reconstruction to restore knee stability and function. Despite advancements in surgical techniques and postoperative rehabilitation protocols, individuals undergoing ACL reconstruction (ACLR) surgery frequently experience quadriceps muscle weakness and deficits in knee extension range of motion (ROM), known as quadriceps lag [1]. Addressing quadriceps lag is critical for restoring full knee function and facilitating a safe return to athletic activities.

Quadriceps lag is a common postoperative complication characterised by the inability to fully extend the knee actively [2]. This impairment is primarily due to neurophysiological disruptions, especially within the neuromuscular pathways coordinating muscle activation. The condition is often exacerbated by joint swelling, pain, and protective reflexes that interfere with full quadriceps engagement. One key contributor to this impairment is Arthrogenic Muscle Inhibition (AMI), a reflexive neuromuscular response where joint trauma leads to altered afferent signalling, impairing voluntary muscle activation [2]. The other factor that induces AMI is pain and inflammation associated with ACLR. This reduces the strength of activation by the quadriceps muscles, leading to incomplete extension of the knee [2]. Knee extension is critically important for patients with ACLR as it is essential for restoring normal gait patterns, achieving full functional recovery, and reducing the risk of subsequent knee injuries [3]. Inadequate knee extension can impair activities of daily living, delay return to sports, and potentially contribute to chronic knee instability or further injury [4].

Traditional rehabilitation methods for addressing quadriceps lag often rely on subjective assessments and passive interventions. However, incorporating objective measures and real-time visual feedback mechanisms into rehabilitation strategies may enhance treatment efficacy and promote optimal outcomes [4]. Real-time biofeedback devices offer a promising approach to monitoring and modifying movement patterns, providing immediate feedback to individuals during rehabilitation exercises [5]. By utilising biofeedback, patients are able to better facilitate neuromuscular re-education and can actively engage in their rehabilitation process, optimising their functional outcomes [6].

Research has shown that biofeedback can improve motor control and muscle activation, leading to better rehabilitation outcomes. While previous research, such as the systematic review and meta-analysis by Ananias et al. [7], has shown that biofeedback interventions significantly enhance quadriceps strength and knee function post-ACLR, the specific impact of real-time visual biofeedback on quadriceps lag remains underexplored. This pilot study aims to address this gap by determining whether real-time visual biofeedback can provide superior rehabilitation outcomes compared to traditional methods. The study focuses on the degree of improvement in quadriceps lag, the consistency of these improvements over time, and whether biofeedback offers advantages in patient engagement and motivation not covered in earlier studies. The real-time biofeedback device used in this study was tested for reliability and validity prior to the effectiveness testing. The intra-rater and inter-rater reliability was excellent, and the criterion validity was high when compared to a universal goniometer.

By integrating real-time visual biofeedback, this study seeks to determine if such an approach can lead to superior rehabilitation outcomes compared to traditional methods, ultimately providing a more objective and engaging way to address quadriceps lag.

This pilot study aimed to assess the effectiveness of an intervention incorporating a real-time visual biofeedback device for measuring quadriceps lag, specifically active knee extension ROM, in participants undergoing ACLR surgery.

Subjects and methods

Study type and design

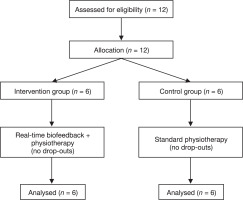

This study was a pilot controlled trial designed to evaluate the effectiveness of a real-time biofeedback device in reducing quadriceps lag in post-ACLR patients. The study was conducted in a clinical setting with participants assigned to either the experimental group (receiving real-time biofeedback along with a standard physiotherapy program) or to the control group (undergoing standard rehabilitation). The flow of participants through the study, including allocation to intervention and control groups, assessments conducted before and after treatment, and analysis, is illustrated in Figure 1.

Recruitment

The study was conducted at Spinex-Spine Care International Physiotherapy Clinic in Surat, India. Potential participants who had undergone ACL reconstruction surgery were approached. During a screening visit, participants were evaluated against the selection criteria. Detailed information about the study was provided, and written consent was obtained. Participants were assured of their right to withdraw at any time, with the understanding that their data would only be analysed if consent for such analysis was given.

Sampling method

A purposive sampling approach, a type of non-probabilistic sampling, was employed to select individuals who met specific inclusion criteria for the study.

Sample size calculation

Given the pilot nature of the study, a sample size of 12 participants was determined to be sufficient to observe potential trends in the effectiveness of the intervention, allowing for an exploratory analysis of the data [8].

Participants

Twelve individuals (7 males, 5 females) aged 19 years or older who had undergone ACL reconstruction (ACLR) surgery were recruited for this study.

Selection criteria

Inclusion criteria for this study required that participants had undergone arthroscopic ACL reconstruction surgery, were at least nineteen years of age, ensuring they could provide their own consent, and had access to a smartphone. Participants also needed clearance from their treating orthopaedic surgeon to perform active knee extension in a high sitting position. Both males and females were considered, provided they were in the rehabilitation phase post-ACL reconstruction surgery, specifically 4–5 weeks post-operative, and willing to give informed consent for voluntary participation. Eligible participants were required to have a stable knee condition, without ligament laxity, allowing for active knee extension. Basic familiarity and comfort with using mobile applications were necessary, along with the capability to interact effectively with a mobile device for real-time biofeedback comprehension. Proficiency in the English language was also required for a clear understanding of the instructions and feedback.

Conversely, the exclusion criteria included recent surgical interventions other than ACL reconstruction, as well as an unstable knee condition with ligament laxity that could compromise the safety of active knee extension. Individuals with severe physical or cognitive impairments that would hinder understanding and compliance were excluded. Participants with contraindications to engaging in usability assessment procedures, such as experiencing severe pain during knee extension, were also not considered for the study.

In the study, the experimental group consisted of six participants, with four males and two females. The participants ranged from 21 to 53 years, with an average age of 31.3 years. The body mass index (BMI) of the participants in this group varied significantly, from 17.1 to 30.2, resulting in an average BMI of 24.1. There were also six participants in the control group, comprising three males and three females. The ages of the participants in this group ranged between 21 and 54 years, with an average age of approximately 31.2 years. The BMI values for this group ranged from 17.1 to 29.7, with an average BMI of 22.5.

Intervention

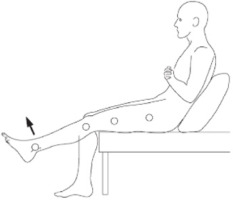

Participants underwent a standard rehabilitation program supervised by a physical therapist. The intervention included active knee extension exercises in a high sitting position performed with a real-time biofeedback device to monitor knee extension ROM. The participants received visual feedback during the exercises to optimise quadriceps recruitment and enhance knee extension.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome of this study was quadriceps lag, measured in degrees using a custom-made wearable real-time biofeedback device before and after the intervention to assess the effectiveness of the biofeedback device.

Wearable device and application

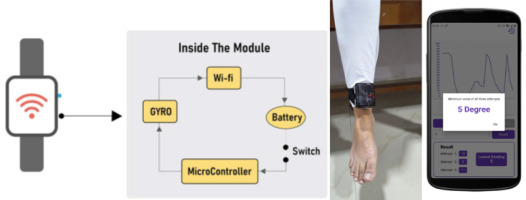

1. Overview of the wearable hardware device

The hardware integrates a 3-Axis Gyro/Accelerometer Microprocessor Unit (MPU 6050) for precise quadriceps lag measurement, a Node microcontroller unit (NodeMCU ESP 8266) with Wi-Fi for communication, a lithium-ion battery for portability, and a Battery Management System (BMS) for safety (Figure 1).

2. Communication with the mobile application

Users pair the device with their Android phone via Wi-Fi. The NodeMCU ESP8266 facilitates secure wireless communication, transmitting real-time data from the wearable device to the real-time biofeedback application. This design ensures mobility and user-friendly lag measurements.

3. Application features (Figures 2 and 3)

The real-time quadriceps lag measurement process began with connecting the application to the hardware via Wi-Fi. Once connected, the application tracked leg movements in real-time, allowing the user to visualise the data through a real-time graph. This setup facilitated accurate monitoring of the knee extension during the rehabilitation exercises.

For limit setting and notifications, the initial degree of active knee extension allowed in the high sitting position was set according to the doctor’s recommendation. The application sent notifications when the set limit was reached, and alarms alerted users to cease leg movements that exceeded the specified angle. This feature ensured that the exercises were performed within safe and effective parameters.

Data recording and storage were managed efficiently within the application. Patient identity number and quadriceps lag data were saved and organised by date for easy reference. The application also generated downloadable PDF reports, which could be used for further analysis and study, providing a comprehensive record of the rehabilitation progress.

To ensure accuracy, multiple attempts were made to measure the quadriceps lag. Three attempts were conducted, and the minimum lag recorded among these attempts was considered as the final quadriceps lag for that date. This method ensured that the most accurate measurement was used for tracking progress and making informed adjustments to the rehabilitation program.

Device testing and validation

Prior to assessing the intervention’s effectiveness, the biofeedback device was assessed for reliability and validity in 20 post-ACL reconstruction participants. The device showed excellent intra-rater reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.960–0.995; ICC = 0.827–0.976) and inter-rater reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 1.000). A high correlation with a universal goniometer (Pearson r = 0.822, p =.000) established the criterion validity of the device in measuring quadriceps lag. These results are being submitted for publication.

Procedure

Participants who met the inclusion criteria were recruited for the study, and informed consent was obtained from each individual. Demographic and medical details were collected to ensure all necessary information was documented. Participants were assigned to the experimental and control groups sequentially as they enrolled in the study. Each group consisted of 6 participants.

During the orientation phase, participants were familiarised with the biofeedback device. This device utilised an accelerometer and gyroscope to measure knee extension range in real-time while in a high sitting position.

In the biofeedback sessions, the participants were guided through the device setup and performed active knee extensions. The real-time data was transmitted via Wi-Fi and displayed on a mobile application interface, allowing participants to see their progress instantly.

Upon completion of the sessions, a debriefing session was conducted to address any questions or concerns the participants might have had. This debriefing was carried out by the investigators.

For the intervention, the participants in the experimental group underwent a standard rehabilitation program, which included standard physiotherapy in addition to knee extension exercises performed with the real-time biofeedback device. The biofeedback device was securely fastened just above the ankle joint and connected to a mobile application via Wi-Fi. In a high sitting position with the trunk inclined backwards and supported (Figure 4) the participants performed knee extension exercises starting from 90° of flexion.

Table 1

Summary of the standard physiotherapy program

The mobile application displayed a real-time graph and readings of active knee extension, providing visual feedback and a target to achieve full knee extension.

Each participant in the experimental group performed 10 repetitions per set, with a total of 3 sets per session, over a span of 10 days. The control group received a standard rehabilitation protocol similar to the experimental group but without the biofeedback component. The standard rehabilitation protocol, as referenced in sources [9], included the exercises and therapies summarised in Table 1.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted to evaluate the baseline characteristics and intervention effects. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess the normality of the continuous variables, including age, BMI, and pre-treatment quadriceps lag. Variables following a normal distribution were analysed using parametric tests, such as independent t-tests for between-group comparisons of age and BMI. Non-parametric tests were applied to variables that did not meet the assumption of normality, including the Wilcoxon Signed-Ranks Test for within-group changes in quadriceps lag and the Mann–Whitney U-test for between-group comparisons of improvements. Categorical variables, such as sex and the affected side, were analysed using chi-squared tests. To determine the magnitude of the intervention effect, effect sizes were calculated using Cohen’s d. All statistical tests were performed at a significance level of p < 0.05.

Results

The baseline characteristics were assessed for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Age (p = 0.294) and BMI (p = 0.191) followed a normal distribution, while pre-treatment quadriceps lag did not meet the assumption of normality (p = 0.027). Based on these results, parametric tests were applied to age and BMI, and non-parametric tests were used for quadriceps lag and intervention effects. Detailed statistical results are provided in Tables 2–4.

Table 2 summarises the distribution of participants by gender, affected side, age, BMI, and pre-treatment quadriceps lag. Both groups were demographically similar, with no significant difference in gender (p = 0.845), affected side (p = 0.623), age (p = 0.531), BMI (p = 0.685), or pre-treatment quadriceps lag (p = 0.231), thus ensuring comparability at baseline.

Table 2

Baseline characteristics of participants

Baseline characteristics such as age, BMI, and pre-treatment quadriceps lag were evaluated to establish group comparability. The experimental group had a mean age of 36.33 years (SD = 13.0), whereas the control group had a mean age of 33.83 years (SD = 11.1), with no significant difference (p = 0.531). The mean BMI of the experimental group was 25.2 kg/m2 (SD = 4.9), and that of the control group was 23.63 kg/m2 (SD = 4.4), with the difference between the groups not being significant p = 0.685). Pre-treatment quadriceps lag was similar between the groups, at 14.50° (SD = 5.9) and 16.33° (SD = 6.9), respectively (p = 0.231). The results thus assure the comparability of the groups as a solid foundation for evaluating the effectiveness of the intervention.

The experimental group showed significant improvement, with a mean (standard deviation) change from 15.50 (2.811) to 1.83 (1.329), while the control group also experienced a change, with a mean (standard deviation) change from 14.50 (1.329) to 6.00 (1.789). The Wilcoxon Signed-Ranks Test, which was used to compare pre- and post-intervention outcomes within each group, revealed statistically significant improvements in the pre- to post-intervention quadriceps lag in the experimental group (Z = –2.207, p = 0.027), while the control group also showed a significant, but smaller, improvement. This suggests that the intervention had a positive effect on the outcomes measured in the experimental group, supporting the efficacy of the treatment.

Table 5 presents the results of the Mann–Whitney U-test comparing the differences in outcomes (pre-post) between the experimental and control groups. The experimental group (Exp) showed a mean difference of 13.66 with a standard deviation of 3.72, while the control group (Con) had a mean difference of 8.50 with a standard deviation of 2.66.

The Mann–Whitney U-test results indicate a statistically significant difference between the two groups (U = 5.500, Z = –2.023, p = 0.043), with the experimental group showing greater improvement. The inclusion of mean and standard deviation values further emphasises that the experimental group not only had higher ranks but also had a higher average improvement compared to the control group, with less variability in the control group. This supports the efficacy of the intervention in the experimental group, leading to significantly better outcomes as compared to the control group.

Table 3

Baseline comparison by group

Table 4

Within-group comparison using Wilcoxon signed-ranks test with mean and standard deviation

Table 5

Between-group comparison using Mann–Whitney test with mean and standard deviation

| Grouping variable | n | Mean ± SD | Mean rank | Sum of ranks | Mann–Whitney U | Z | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | 6 | 13.66 ± 3.7 | 8.58 | 51.50 | 5.500 | –2.023 | 0.043 |

| Control | 6 | 8.50 ± 2.6 | 4.42 | 26.50 | |||

| Total | 12 | – | – | – |

Effect size: For the experimental group, the effect size was calculated as 3.671, indicating a large and meaningful improvement in knee function attributable to the biofeedback intervention. For the control group, the effect size was 3.189, reflecting a significant improvement as well, though slightly less pronounced compared to the experimental group.

Discussion

This pilot study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of an intervention involving a real-time biofeedback device for improving quadriceps lag, specifically active knee extension ROM, in individuals undergoing ACLR surgery. Twelve participants (7 males, 5 females) aged above 18 years who had undergone arthroscopic ACLR surgery were recruited. The intervention consisted of a structured rehabilitation program supervised by a physical therapist, incorporating active knee extension exercises with real-time biofeedback to monitor knee extension ROM. The study aimed to provide insights into the effectiveness of biofeedback interventions in improving knee function and quadriceps lag in individuals undergoing ACLR surgery.

The findings of this pilot study suggest that the intervention incorporating a real-time biofeedback device is effective in improving quadriceps lag, specifically active knee extension ROM, in individuals undergoing ACLR surgery. Our results showed significant improvements in knee extension range post-treatment, as indicated by a reduction in quadriceps lag. Both the experimental and control groups demonstrated improvements; however, the experimental group, which received the biofeedback intervention, exhibited greater reductions in quadriceps lag compared to the control group. The results of our study are consistent with those reported by Luc-Harkey et al. [10], which highlighted the effectiveness of real-time biofeedback in improving knee extension mechanics in individuals after ACLR. Similar to our findings, Luc-Harkey et al. [10] found that biofeedback interventions led to significant improvements in knee extension ROM and quadriceps function, suggesting that biofeedback may be a valuable tool in ACLR rehabilitation.

The demographic characteristics of our participants align with previous research on ACL injuries, showing a higher prevalence among males [10, 11]. However, previous studies have highlighted that female athletes are at a greater risk for ACL injuries due to biomechanical and neuromuscular factors [12], while sports such as elite football show a consistently high incidence of ACL injuries across both genders [13]. Additionally, the predominant use of hamstring grafts in our study is consistent with the trend towards increased utilization of this graft type due to its favourable outcomes and reduced donor site morbidity [14].

The intervention involving active knee extension exercises with real-time biofeedback demonstrated significant improvements in knee extension ROM. This is consistent with previous studies indicating the effectiveness of biofeedback interventions in improving quadriceps function and knee ROM following ACLR surgery [15, 16]. These studies also emphasise that early structured rehabilitation and allograft considerations can influence recovery outcomes [15]. Our results are consistent with previous studies, such as those by Delitto et al. [17] and Snyder-Mackler et al. [18], which demonstrated the effectiveness of electrical stimulation and biofeedback interventions in improving quadriceps function and knee ROM following ACLR surgery. This highlights the potential for combining biofeedback with other modalities for optimal quadriceps re-education [17, 18].

Real-time biofeedback enhances rehabilitation by providing immediate, objective data on joint movement, which helps patients adjust their actions in real-time to achieve better out comes. By displaying real-time graphs and readings of knee extension, the biofeedback device allows patients to see their performance instantaneously, enabling immediate correction and making necessary adjustments during the exercise. This visual feedback sets clear targets, such as full knee extension, motivating patients to strive for complete extension, which is crucial for reducing quadriceps lag [15]. Additionally, seeing the immediate impact of their movements encourages patients to engage their quadriceps muscles more effectively. Over time, this repeated activation helps re-educate and strengthen the neuromuscular pathways [16]. Continuous feedback ensures that the exercises are performed correctly and consistently, promoting better muscle memory and more effective rehabilitation.

The interactive nature of biofeedback keeps patients engaged in their rehabilitation process, leading to higher adherence to rehabilitation protocols and improved outcomes [6]. Patients can track their progress over time, which provides positive reinforcement and encourages continued effort and improvement. Biofeedback also ensures that exercises are performed with the correct form and intensity, reducing the risk of compensatory movements that can impede progress [5]. Moreover, biofeedback provides precise measurements of knee extension ROM, enabling accurate assessment of quadriceps lag and progress over time [15]. This allows therapists to make data-driven decisions to modify the rehabilitation plan based on the patient’s performance, leading to more effective and individualised treatment. By integrating these elements, real-time biofeedback facilitates a more effective rehabilitation process, ultimately leading to significant improvements in quadriceps lag and overall knee function.

The visual feedback provided during exercises likely facilitated optimised quadriceps recruitment, leading to enhanced knee extension and reduced quadriceps lag. Furthermore, biofeedback facilitates improved proprioception – the body’s ability to sense its position and movement in space. The continuous feedback provided by the biofeedback device helps patients become more aware of their joint movements and muscle activations, leading to more precise and controlled movements. This heightened proprioceptive feedback is vital for restoring normal movement patterns and reducing compensatory movements that can impair recovery [19, 20]. This finding is in line with a study by Chaput et al. [21], which also noted that biofeedback significantly improves proprioception and muscle activation in ACLR patients [21,22].

Motor control theories, such as Schmidt’s Schema Theory, emphasise the role of feedback in refining movement patterns through practice. In rehabilitation, biofeedback acts as augmented feedback that guides patients by providing real-time data on their performance. This feedback can strengthen motor learning by helping individuals adjust their movements based on immediate cues. Biofeedback supports neural plasticity by facilitating the brain’s ability to reorganise neural pathways, especially after an injury like ACLR surgery, where muscle inhibition often occurs. Moreover, Dynamic Systems Theory highlights that motor learning results from the interaction of multiple systems – neurological, musculoskeletal, and environmental – which biofeedback targets by enhancing muscle coordination and movement efficiency. The Closed-Loop Theory of motor control suggests that continuous feedback optimises motor skills by correcting errors in real-time, making biofeedback a key tool for improving motor control during rehabilitation exercises [23, 24]. The frequency of applying this biofeedback application – daily versus interval-based – may influence its effectiveness in motor learning. Daily biofeedback provides consistent, real-time performance feedback, which may lead to quicker neuromuscular re-education and faster motor learning by reinforcing motor patterns more intensively. In contrast, interval use (such as several sessions per week) may allow for a longer consolidation of learned movements, potentially leading to more durable but slower improvements. The choice of biofeedback frequency should depend on the specific rehabilitation goals and the stage of recovery, with daily use being more beneficial in early rehabilitation phases to re-establish muscle activation patterns and interval use being more effective in later stages to refine motor skills and promote long-term retention.

Our study’s statistical analyses revealed significant differences in post-treatment quadriceps lag between the experimental and control groups, with the experimental group exhibiting lower quadriceps lag scores. This indicates that the intervention incorporating the real-time biofeedback device was more effective in improving knee extension ROM compared to standard rehabilitation protocols. Similar findings were reported in studies on wearable biofeedback and accelerated rehabilitation exercise [16, 17]. In addition, early studies highlighted that electrical stimulation combined with voluntary exercise enhances quadriceps strength and functional recovery, supporting our findings [17, 18]. Quadriceps strength asymmetry following ACL reconstruction also significantly alters knee biomechanics and functional performance, further validating the role of targeted interventions like biofeedback [19–22].

The effect sizes calculated for the mean differences between pre-treatment and post-treatment sessions were substantial. These large effect sizes indicate that the improvements achieved are not only statistically significant but also clinically meaningful. The substantial effect sizes suggest that the biofeedback intervention provided considerable benefits to knee function, which can significantly enhance both daily activities and sports performance.

The real-time biofeedback device used in our study is designed to be effective at various stages of the rehabilitation process. In the early post-operative phase, the device assists patients in establishing correct movement patterns by providing immediate visual feedback on knee extension range and muscle activation. This ensures that exercises are performed with proper technique from the start. As patients progress to the intermediate phase, the device continues to play a vital role by supporting the enhancement of muscle strength and coordination. Continuous feedback on knee extension allows patients to monitor their improvements and adjust their efforts accordingly, ensuring optimal muscle engagement. In the later stages of recovery, the device aids in refining motor control and optimising functional movements. By helping patients achieve their knee extension goals and align their movements with functional activities, it ensures a smooth transition from rehabilitation exercises to everyday tasks. Finally, as patients approach discharge and enter the maintenance phase, the device helps in reinforcing correct movement patterns and preparing them for independent exercise. It provides ongoing feedback, enabling patients to track their progress and maintain their gains. Overall, the real-time biofeedback device supports a comprehensive rehabilitation process, enhancing both immediate recovery and long-term outcomes.

Combining biofeedback with electrostimulation can further enhance rehabilitation outcomes. Electrostimulation techniques, such as neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES), have been shown to improve muscle strength and activation post-ACLR surgery [16]. When used in conjunction with biofeedback, these modalities can provide comprehensive neuromuscular training, targeting muscle activation deficits and promoting optimal muscle recruitment patterns. This combined approach may accelerate recovery and improve functional outcomes, offering a synergistic effect in rehabilitation protocols.

Biofeedback devices, while initially costly, offer long-term benefits that can outweigh their initial investment. By facilitating faster recovery and reducing the risk of complications or re-injury, biofeedback helps minimise the need for prolonged rehabilitation sessions and potential revision surgeries [17]. This cost-effective approach not only reduces healthcare expenses but also enhances patient satisfaction and outcomes, making it a viable option in orthopaedic rehabilitation settings.

Biofeedback contributes to neurological rehabilitation by stimulating neural pathways involved in motor control and proprioception. The immediate feedback provided during exercises helps patients improve their motor learning and control, enhancing neuromuscular re-education after ACLR surgery [18]. Physiologically, biofeedback aids in reducing quadriceps lag by promoting optimal muscle activation and coordination, which is crucial for restoring knee function and preventing functional deficits [19]. By targeting specific muscle groups and monitoring their activation patterns, biofeedback interventions address muscle imbalances and facilitate a balanced recovery trajectory [25].

Limitations

We acknowledge that the small sample size limits the generalisability of our findings. The results from this pilot study may not be fully representative of the broader population undergoing ACLR surgery. Also, the fact that all participants were hamstring graft patients, rather than including other types of grafts used in practice, is a limitation that may affect the applicability of our results to patients with different graft types. The absence of blinding in this study could introduce potential bias, affecting the objectivity of the results. The shortterm follow-up period restricts the ability to assess the longterm effects of the biofeedback intervention. Future studies with extended follow-up durations are necessary to evaluate the sustained impact of the intervention on knee function and quadriceps lag.

Future recommendations

Future research directions include the necessity of conducting larger-scale randomised controlled trials to validate the findings more robustly. Extending the follow-up periods is also crucial to comprehensively evaluate the long-term effects of the interventions. Investigations should focus on determining the optimal timing and duration for biofeedback-based exercises to maximise their efficacy. There is also a need to explore individualised biofeedback protocols to tailor interventions to specific patient needs, potentially enhancing outcomes further. These studies should assess not only the immediate effects of biofeedback interventions but also their long-term impact on quadriceps lag and overall knee function. Additionally, extended follow-up periods would allow researchers to evaluate the sustainability of improvements gained through biofeedback and whether these changes contribute to better functional outcomes and reduced reinjury rates over time.

Conclusions

This pilot study suggests that real-time biofeedback devices may be a valuable adjunctive tool for assessing and addressing quadriceps lag in individuals undergoing ACLR surgery. By providing immediate feedback and promoting active engagement in rehabilitation exercises, biofeedback interventions have the potential to optimise quadriceps activation, improve knee extension ROM, and enhance functional outcomes post-ACLR surgery.